Sometimes music is about lineages. The two pieces comprising this weekend’s offering by the San Francisco Symphony highlighted the connections between Mussorgsky, Ravel, Brittan, and Shostakovich. Mussorgsky was Shostakovich’s spiritual father, Ravel was his Mussorgsky’s orchestrator, and Brittan was the dedicatee and conductor for the premier of Shostakovich’s 14th Symphony. In themselves, these connections would be worth exploring, because none of this music happens in a vacuum. The evening opened with Shostakovich’s 14th Symphony, and closed with Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition – both of which are worth considering at length.

Shostakovich’s 14th Symphony isn’t exactly one of his better-known works. Begun in 1966, it premiered in 1969, and finally made it to San Francisco in last week. This not particularly symphonic work was sung by soprano Olga Guryakova and baritone Sergei Leiferkus, accompanied by a handful of violins, cellos, basses, violas and a percussion section. Inspired by Mussorgsky’s Songs and Dances of Death, and drawing heavily on Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde, it is at once an eerie and ponderous contemplation of what Shostakovich believed to be his imminent demise. Houselights were left up so that the audience could read the six pages of poems by Federico Garcia Lorca, Guillaume Apollinaire, Wilhelm Kuchelbecher, and Rainer Maria Rilke that comprised the libretto.

The piece opens with a serpentine violin passage, which is immediately picked up by the basses, and reworked and repeated throughout the work. Olga Guryakova brought a compelling stage presence, intentionally remote and removed, while simultaneously and completely in the moment. During various poems, her performance had some of the same feeling as Brünnhilde’s immolation scene in Gotterdammerung – a comparison that is not entirely off the wall, given that (1) Conlon conducted the Los Angeles Ring just last year, and (2) Leiferkus sings of her as “the Rhine valley’s blond sorceress.” Leiferkus was one of the more mellifluous baritones I’ve heard. Listening to him, one could never imagine that these lower registers could possibly ever be muddy or indistinct so powerfully clear was his performance. Perhaps most gripping was “V turme Santé, as Leiferkus voice alternated with the naked cello, played pizzicato, and basses, which seemed to be played by bouncing the bow off the strings,

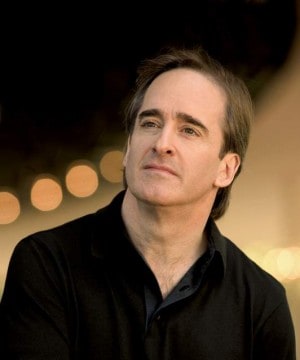

Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition – or at least – the “Tuileries” and “Great Gates of Kiev” sections I know better than almost any piece of music. The heavily edited version of the “Great Gates” I played forty years ago is still on my piano, as is the unedited version. We hear the orchestrated version of Pictures at an Exhibition so frequently, that it’s easy to forget that this was originally written for piano. What we hear is Ravel’s orchestration of the same. However, as Conlon’s program notes remind us, Ravel didn’t have access to Mussorgsky’s original score – so Conlon revisited it, making a few deft changes. These would be inaudible to almost everyone. However, if you ever struggled to nail those stubborn grace notes before sounding the massive ten-finger chords that the piece opens with, the fluidity of Conlon’ openings will come as a delightful surprise. They move lightly together, allegro alla breve.

Technical comments aside, a more interesting question is what is required to make an excellent “Pictures” performance? Like any other over-performed piece, there are certainly enough bad versions out there, with sour trumpets blatting miserably. However, even if you can assume some kind of technical brilliance, where does that take you?

First, each of the ten sections needs to stand alone as a distinct musical experience. The corollary of that is the playful bits in “Tuileries” (Dispute d’enfants après jeux) and the silliness of “Ballet of the Unhatched Chicks” (to which Conlon has restored the original coda) have to be drawn out to create a launching pad for the dread foreboding that opens “Catacombæ,” and then the “Great Gates of Kiev,” which aims for the transcendental with it’s opening directions: “Allegro alla breve. Maestoso. Con grandezza.”

Conlon more than delivered on the majesty and nobility of this piece, so much so that the audience fell over itself in gratitude afterwards at the transformative quality. This was not one of the de rigueur standing ovations that seem to be slowly creeping into the concert hall, after having made themselves at home in the theatre. This was a performance that left many in Davies with tears bucketing down their cheeks.

Conlon authored his own program notes and made remarks from the stage – both of which added immeasurably to the performance. Hopefully he will be back on this stage in the future.

James Conlon conducts the San Francisco Symphony

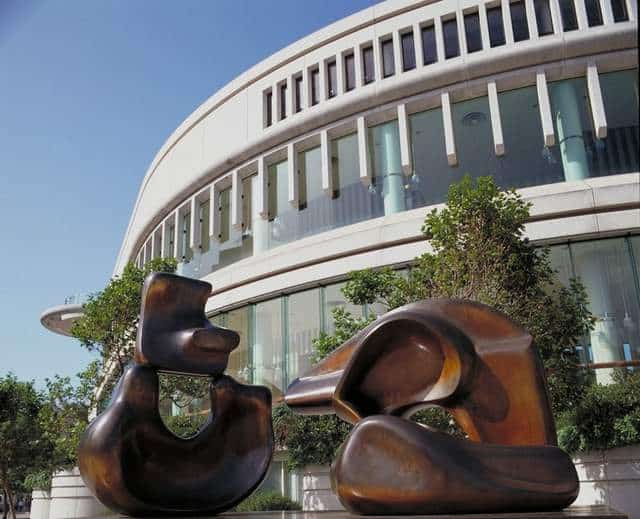

Davies Symphony Hall

5 out of 5 stars (Outstanding – Starkie!)

Conductor: Jame Conlon

Soprano: Olga Guryakova

Baritone: Sergei Leiferkus