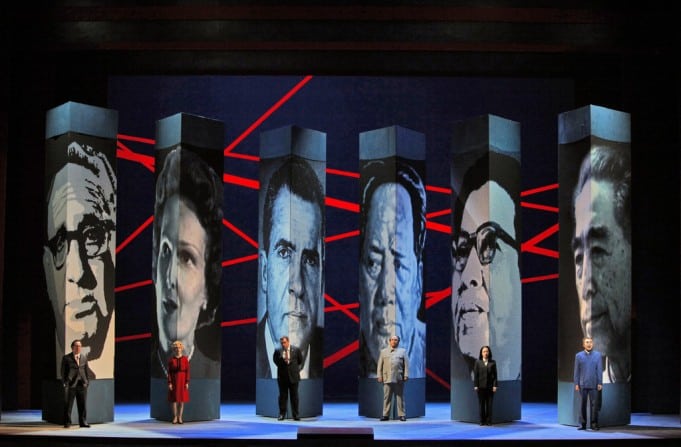

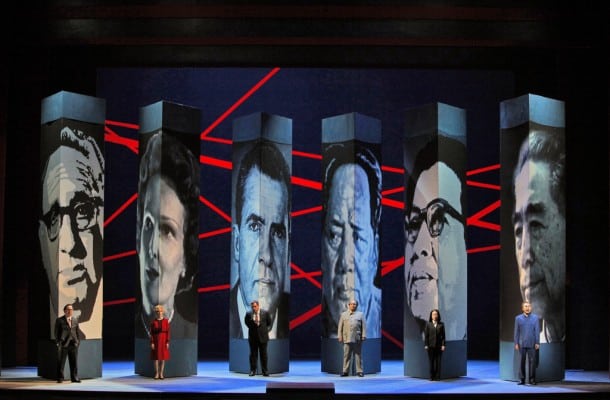

Chen-Ye Yuan (Chou En-lai).

The tantalizing hype surrounding the 1987 opening of Nixon in China was as inescapable to music lovers as the news of Nixon’s 1972 trip was to everyone else. Adams had written a quintessentially American opera. This was shocking in itself; however, in using Nixon’s trip as subject matter, Adams and librettist Alice Goodman revealed a deeper appreciation of the mythologies that inform us. All the 1987 hype made the harsh criticism after the Houston premiere (Henahan’s New York Times review opened with the words “That was it? That was Nixon in China?”) entirely mystifying. While Nixon went on to enjoy a life of its own, it’s only now – 25 years after it first opened – that is finally premieres in San Francisco. This alone makes it one of the most important openings in quite some time.

The spellbinding opening of Act One demonstrates how the San Francisco Opera continues to seamlessly integrate video with conventional sets. Nixon opens with a projection of Air Force One cutting through clouds, setting down, and rotating so that the nose of the plane directly faces the audience from stage right. As the scrim rose, the audience was wowed to find a plane in place of video projection, from which Nixon (baritone Brian Mulligan) bounded down with outstretched hand to greet Chou En Lai (tenor Chen-Ye Yuan). Some time back, the opera announced that it would rely more on video as a cost-saving measure – and Nixon continues to show that this strategy effectively expands the possibilities of staging while retaining its authenticity.

The first act was the strongest in this 3 hour, 20 minute opera, as it embraces the mythology enacted by both Mao and Nixon. This mythology speaks to both the historical moment as well as the individual actors. In his Memoirs, Nixon recounts consulting the former French Minister of Cultural Affairs Andre Malraux before the trip. Malraux reminded Nixon that he would be meeting a colossus, saying “You will meet a man who has had a fantastic destiny and who believes that he is acting out the last act of his lifetime. You may think he is talking to you, but he will in truth be addressing Death.” This sense of historical moment informs the entire first act ,and propels it forward just as much as Adam’s repeated musical sequences. Cognizant that the moment transcends the person, Nixon sings “News, news, news… has a kind of mystery.” Adams and Goodman understand Nixon as a figure of great tragedy because just as soon we see him rhapsodizing about the historical transcendence of the moment, he lapses into a paranoid fit, singing “the rats, the rats, the rats they chew the sheets.”

Mulligan comfortably takes in both faces of Nixon. Although his portrayal of Nixon has cartoonish moments with iconic jowl jiggles, this offers the audience moments of recognition, rather than moments of mockery.

Air Force One touches down outside Beijing.

Mao was performed by baritone Simon O’Neill. Combining athletically vigorous vocal passages (“Founders Come First, then Profiteers”), while portraying the elderly Mao presented challenges for any singer. O’Neill’s sense of Mao’s great age was inconsistent as he moved from athletic vocal performances to moments when he obviously settled back into Mao’s stiff and constrained joints.

The second act of Nixon in China has always problematic to me as it involves a fantasy in which the principals Pat Nixon and Henry Kissinger become actors in a propaganda ballet offered for their entertainment. This ballet, entitled The Red Detachment of Women, was presented to the Nixons during their trip. In the opera, Kissinger becomes an actor who rapes and beats a young peasant woman, much to the horror of Pat Nixon, who storms the stage to stop the action.

MORE SAN FRANCISCO OPERA:

The Steve Silver Foundation announces Scholarship for the Arts winners

2012 Schwabacher Debut Recitals at San Francisco Opera Center

This scene seemed so fantastical that I turned to Nixon’s Memoirs for his impressions of the event from which the fantasy is derived. Nixon writes that although he didn’t like the propaganda of the ballet (and was annoyed by Chiang’s Ching’s needling him, asking why Jack London committed suicide), he states “after a few minutes I was impressed by its dazzling technical and theatrical virtuosity. Chiang Ching had been undeniably successful in her attempt to create a consciously propagandistic theatre piece that would both entertain and inspire its audience. The result was a hybrid containing elements of opera, operetta, musical comedy, classical ballet, modern dance and gymnastics.”

Patrick Carfizzi (Henry Kissinger), Maria Kanyova (Pat Nixon), Brian Mulligan (Richard Nixon), Simon O’Neill (Mao Tse-tung), Hye Jung Lee (Madame Mao) and Chen-Ye Yuan (Chou En-lai).

Nixon’s comments on the real event are an excellent description of the fantastical one. This act was longer than I’d imagined it would be, leaving room for all the elements that Nixon describes. It closed with Soprano Hye June Lee’s coloratura aria “I am the Wife of Chairman Mao,” which left the audience breathless with its ferocity. For all the vocal pyrotechnics of the evening, her performance transformed could have been a painfully long act, and transformed it into spellbinding drama.

In Act III, the principals reflect upon what has taken place, and provide more context about how this fits in their personal lives. Parts of this act are difficult to understand, as various actors sing different parts simultaneously. As throughout the play, Chou En-lai (Chen-Ye Yuan) emerges as the true philosopher. Yuan sings alone, with a ghostly wistfulness and a measured pacing in “I am Old and Cannot Sleep,” singing “How much of what we did was good?”

San Francisco Opera’s production of Nixon in China succeeds (in Adam’s words) in lifting “the story and its characters, so numbingly familiar to us from the news media, out of the ordinary and onto a more archetypal plane.” The only regret is that it took them twenty five years to do so.