I’m all for entrepreneurship, and I’ve got to hand it to Dalton Caldwell. He’s just raised over $700,000 using his own “Kickstarter-like” crowd-funded campaign for a service, App.net, that could very well change the economics of Web 2.0 companies and services. There’s only one problem:

I have no idea what App.net does.

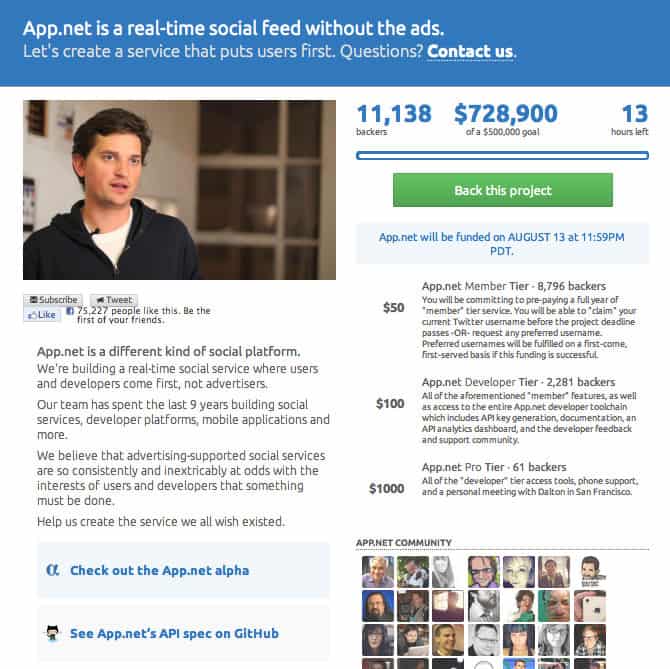

Granted, that’s likely because I’m not a target user. With over 11,000 backers his idea seems to have caught on with at least a handful of potential users — many of whom I’m guessing are developers fed up with Twitter — who value the idea of a paid, Twitter-like service to build apps leveraging a real-time stream (here’s a link to the alpha which looks like… Twitter but without the scale).

Watching Dalton explain the concept in the video raised a few questions, and observations.

1. The concept for App.net is focused on what it is NOT

App.net is not free. It’s a paid service. You’ll know that in no uncertain terms by the time you finish watching Dalton’s pitch. You’ll also get the vague notion that App.net will not “let you down” like so many other Web 2.0 services. You know the ones with no value that we still use day-to-day like Facebook, Twitter, Google, and Yelp. The problem here is I found the explanation wanting in specifics. What exactly is App.net? Why would I prefer paying for it over using Twitter or even Google+? There’s a quick explanation at the beginning of the video about App.net being “a real-time feed, an API.” Then there’s the tag line: “a different kind of social network.” That’s it. The rest of the pitch has to do with the fact that it’s a paid service. My suspicion — born out of a marketers naivety — is that the true value will be exposed via third-party apps that are built on top of its API.

2. Error in Logic: Just because a company charges for something does not mean it will be customer focused

In this era of freemiums, Dalton does propose an interesting, counterintuitive idea. That is, when companies charge for a service the focus is entirely on the customer because economic incentives are aligned. On the other hand, with ad-supported businesses, he claims, “all the financial incentive is to please advertisers, not end users.” But that’s absolutely not true. Businesses that rely on advertisers need customers or eyeballs as the case may be to command advertising premiums. Without customers, you don’t sell ads. Just because a business is free does not mean it’s not customer focused. Take Yelp. It’s free. Does it work? Ask its users and you’ll get a hugely loyal, strong response. Now take United Airlines. That’s a paid service. Ask someone who flys a lot what they think of UA…

3. Does Kickstarter have any patents/copyrights?

When I went to the App.net site I thought I was on Kickstarter. The format is virtually identical. There’s a project page, followed by a pitch, and on the right is the information we’re used to seeing on a funding page: number of backers, funding goal, time remaining, etc. It looks so similar that TechCrunch even confused it with the real thing. But this is not Kickstarter. This is “Kickstarter-like.” Which means over 11,000 people are giving their money directly to Dalton Caldwell. Good on him. He avoids the fees, and gets the funding straight from the source, sans middle man. There’s a certain level of trust assumed by those investing; though Dalton does confirm on this blog post he’ll be using Stripe as a trusted third-party to handle payments.

But none of this apparently matters to the early backers. Perhaps they see an opportunity to re-invent Twitter. And maybe they’ll be right. Or App.net could very well be a niche alternative with specific applications and use cases that Twitter could never touch because of its sheer size, and need to please advertisers. In fact, there’s already a rapidly growing directory of third party tools and apps built on App.net. Given this early momentum plus growing discontent with Twitter’s tightening API, could give the service enough of a boost to get it off the ground.

Ultimately this could be a game of trade-offs. Don’t want to be beholden by Twitter’s constantly changing and restrained API? Then you can turn to something like Api.net. The risk, of course, is that whatever you build won’t ever reach critical mass because the users just won’t be there (unless I’m reading this wrong). Most companies I suspect will prefer the current route: accept some business risk by building on Twitter (or Facebook) so that they can tap into massive audiences.

There’s a dodgy aspect to the whole deal. Regardless, it will be interesting to see how App.net plays out. After funding closes the company will benefit from a built-in, generously sized alpha/beta customer base. Because there’s a significant number of backers, Dalton has more than likely smartly identified a unique market opportunity not immediately obvious or reachable to nearby titans. Since each of the earlier investors will want to see the project (“movement”) succeed no doubt each will be trumpeting the heck out of the thing on… Facebook, and Twitter.