It’s hard not to relate to the trials and tribulations of the lead characters in Chinglish. For anyone that’s struggled with the cultural divide, there’s a familiar ring to seeing two people slide into an increasingly frenetic game of charades — arms waving wildly — when it comes to communicating; even when it means saying something as simple as I Love You.

As I sat watching this marvelous season opener at the Berkeley Rep I kept thinking back to the time I ran North American marketing for a Japanese software company. My boss, who was based in Tokyo and only made important decisions over nigiri at the finest sushi houses in town, did not speak English – or at least not the way I perceived the situation. I did not (and sadly still don’t) speak Japanese. Every meeting required a translator, as did my original job interviews. There was plenty of double happiness in the following months. I learned to keep my arms still in meetings. I was always cognizant of rank, and of who sat where in a conference room and how conversation flowed. One trip to Tokyo I presented my boss with the grand marketing plan for America. He listened, nodded, seemingly in agreement throughout. I sweated. Would he approve such a large budget? At the end I awaited his reaction, and verdict. After an agonizingly long pause, he said “Hmmmmmmm,” and then, “Yes, you don’t!” I waited for clarification, but realized none was coming – or even necessary. I headed back to Palo Alto not really sure if I had a budget. Over time I learned his response was akin to “baby steps.” So, yes, spend money, but, no, not all at once. What appeared as double entendre turned out to be perfectly sage advice.

Hwang creates an intimate dance between the protagonist and those that appear to help and hinder him at the same time, while painting a broader undercurrent of political tension: America, the fading superpower, and China, the mighty Red.

If only I were so lucky as to have the super titles available as seen in David Henry Hwang’s staging. They float above the actors and are ingenious in capturing comedic misconceptions of even the tiniest of linguistic slips. Meanwhile, below, the story centers around translation and sign specialist Daniel Cavanugh (Alex Moggridge) from Cleveland — aka a “small farming village.” Following the misfortunes of his company domestically he seeks opportunity abroad in the form of a sign deal for the new cultural arts center project in the small town of Guiyang, China. A minister (Larry Lei Zhang) and his aid (Michelle Krusiec) want to avoid the embarrassments of poorly (and often offensive) translations seen at similar projects in Shanghai, and indeed across the land (“Fuck the certain price of goods.”)

Hwang takes the audience through a first-hand journey of doing business in China by having Daniel share with us his learnings (rule #1 – always bring your own translator) and then taking us along for the ride. Daniel opens with an uproarious presentation of translations gone wrong. Then he rolls back the clock, and we’re eavesdropping on a dinner meeting where he signs on a consultant (Brian Nishii) who specializes in doing business in China.

Straightforward at first blush, the “deal” turns out to be fraught with complexity and plenty of back doors. Sex, corruption, and even Enron conspire to potentially send Ohio Signage Company into the ground.

There’s many layers here. Hwang creates an intimate dance between the protagonist and those that appear to help and hinder him at the same time, while painting a broader undercurrent of political tension: America, the fading superpower, and China, the mighty Red.

Alex Moggridge delivers a superb performance as the good-hearted and continually befuddled mid-westerner just trying to save his business (and family) amidst the stubbornness of a foreign culture. He does well in this type of role, and by my estimation this turn at Berkeley Rep is the biggest of his career. I last saw him in the shag-a-delic sex romp Boeing Boeing at Center Rep where he delivered a similarly amusing, perpetually flustered performance.

Equally impressive is Michelle Krusiec as the slinky, mysterious vice-chair of the cultural department. She could be right out of a James Bond film. A sexy seductress one moment, and a powerful Government agent the next, Krusiec keeps us contemplating her motives with a sly performance that never slips into caricature.

Then there’s the set. It’s a dual-rotating masterpiece of mind-boggling detail. During transitions the action continues — actors are seen entering elevators, walking through revolving doorways, changing their clothes. I can only imagine the technical gymnastics happening backstage. If there’s one minor causality of having such a large contraption is that it takes away the depth of the stage. All the action is instead up front. The intimacy, in this case however, works well and brings us further into a world of mangled words.

Should you see Chinglish?

Yes, you don’t!

And:

Always bring your own translator.

Always bring your own translator to

@berkeleyrep RT@starkinsider: Review: ‘Chinglish’ say “Yes, you don’t!” https://www.starkinsider.com/2012/08/review-chinglish-berkeley-repertory-theatre.html— Clinton Stark (@clintonstark) August 30, 2012

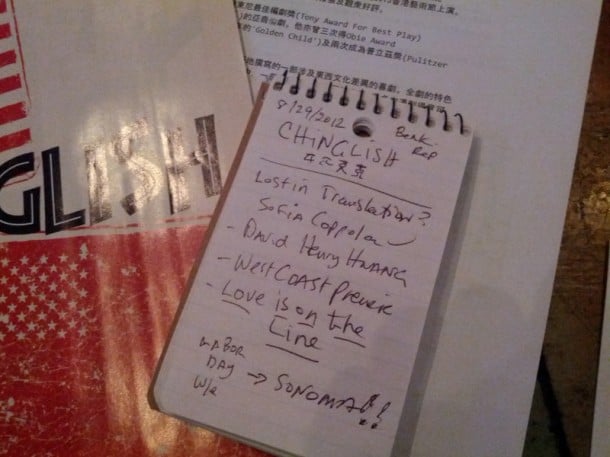

Spotted in the Berkeley Rep men’s room: