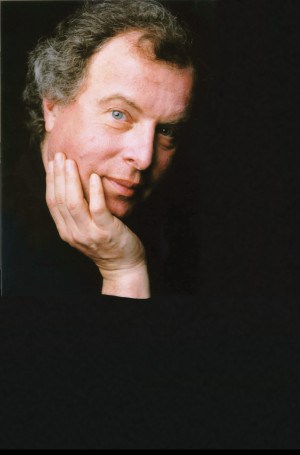

Bach’s Prelude in C Major from the “Well Tempered Clavier Book One” might be the classical equivalent of Stairway to Heaven. Almost every beginning piano student has a go at this one, as the fluid arpeggios are easy for small fingers. What a different experience to hear it played by the master! There’s nothing so humbling as hearing a piece whose every note you intimately know played by András Schiff.

Bach’s Prelude in C Major from the “Well Tempered Clavier Book One” might be the classical equivalent of Stairway to Heaven. Almost every beginning piano student has a go at this one, as the fluid arpeggios are easy for small fingers. What a different experience to hear it played by the master! There’s nothing so humbling as hearing a piece whose every note you intimately know played by András Schiff.

As usual, I’m getting ahead of myself. Prelude in C Major was the encore that Schiff treated the audience to at the San Francisco Symphony after they refused to let him go on Sunday afternoon when he played “The Well Tempered Clavier, Book II.” The aforementioned Prelude in C Major was from “Book I,” which Schiff performed a mere two weeks ago, thus bringing the two concerts full circle.

Both books of the “Well Tempered Clavier“ consist of preludes and fugues written by Bach in every major and minor key. Thus, the first prelude and fugue pair is in C Major, the second is in C Minor, the third in C# Major, the fourth in C# minor, and so forth. Like many of Bach’s pieces, such as the “Notebook for Anna Magdalena Bach,” which contains Minuet in G and Musette, known to every piano student, the “Well-Tempered Clavier” was a series pedagogical exercises “for the Use and Profit of Musical Youth” ranging from the very easy Prelude in C Major in “Book One” to the tricky fugue of the No. 24 in B Minor in “Book II.”

Schiff held the audience in his hands on Sunday afternoon as he worked his way, sans sheet music, through the entire “Book II.” All the elements at the heart of a Schiff performance were on display. Every single note of complex ornaments was individually articulated. His crystalline clarity enabled the listener to “listen through” even the densest baroque textures played at lightening-like speed. Rhythms that one never considered, such as that of Prelude of No. 15 in G Major, took on a new importance as they drove the piece home in ways I’ve never heard. His elegant gestures made unremarkable pieces (such as the aforementioned Prelude in C Major) seem incredibly profound. Passages that I’d always faked my way through now seem like mumbling loudly in middle school French.

In a video appearing on the SF Symphony web site, Schiff takes on the worthy issue of why it’s legitimate to play this music on the piano, which was barely available in Bach’s time:

This is a worthy question. In Harold C. Schonberg’s dated (1963), but still valuable volume “Great Pianists from Mozart to the Present,” Schonberg points out that “the history of piano playing begins with Mozart and Clementi,” and “even Mozart did not begin to concentrate on piano until the middle 1770’s.” Schonberg reminds us that Bach died in 1750, which marked “music’s shift from church to salon, from fugue to sonata.” He astutely points out that this “new music did not want to think. Rather it wanted to be charmed.” Certainly the elements that make Bach intellectually interesting shift. However. Schonberg also points out that Bach had access to pianos built by Gottfried Silberman as early as 1736. This gives merit (which hardly need to be given) to Schiff’s argument. If “Clavier” includes all keyboard instruments, by definition, it must include those early pianos built by Silberman.

Schiff will return to San Francisco to play Bach’s English and French suites at Davies in April, 2013, as part of a two season residency. The San Francisco Classical Voice notes that “the last time J.S. Bach’s keyboard works received such major exposition was 80 years ago in Berlin, when Claudio Arrau performed them ‘all’ (an imprecise term for this limitless canon) in 14 recitals.” This seems to be a reasonable approximation of the truth. More importantly however, Schiff makes this music exquisitely accessible, for as he says “Bach is one of us. The best of us – but one of us.”