MY RELIGION IS MONEY AND GUNPOWDER.

In the wildly successful video game BioShock (2007), a ruthless capitalist builds an underwater world. Its charismatic yet mysterious creator, Andrew Ryan, despises socialism – “Is a man not entitled to the sweat of his brow?”. His ideals are more in line–as game designers have revealed in interviews as inspiration for the character–with the likes of Ayn Rand and Howard Hughes. As the story unfolds we’re exposed to his bold vision, and haunting proclamations. Ultimately his world comes crashing down, a waterlogged dystopia of sorts ensues. Chaos reigns. But, the extremism of Ryan does make us think: What is right and what is wrong?

Earlier scenes in the play will no doubt draw comparisons to Downton Abbey. Though the action takes entirely upstairs, the class system is obviously fodder.

Though clearly pegged as a villain, Andrew Ryan’s forebear in George Bernard Shaw’s Major Barbara may be less so. Industrialist Andrew Undershaft is just as opinionated, but a dollop of dastardly likability and convincing logic does leave us, witting or not, questioning morality, religion, and the machinations of political systems. A.C.T. (American Conservatory Theater) in San Francisco have smartly “re-imaged” the classic play. At the premiere last evening, the themes that Shaw so presciently explored in 1905 came crashing across the audience like so many tidal waves. Or, maybe, that was a series of relentless, mind numbing explosions; our craniums were at the Irish playwright’s mercy.

His counterpart didn’t stand a chance. Turns out his daughter, an idealist and savior to the poor, is simply no match. I wonder if Shaw intended the playing field to be so lopsided? He’s been described as an “ardent” socialist and yet in his dialog he creates such a compelling force in Undershaft that we can’t help but think there’s merit in the supposition: is charity and government ultimately not bought and paid for big business? Enterprise. Profits. That’s what moves the world forward, much as we’d prefer to believe otherwise. Or, as he responds when asked to describe his religion: money and gunpowder. By elevating the central figure in this play, however, Shaw gives us a caricature suitable for satire.

Unfortunately Major Barbara starts slow. It’s not until the third act, when we’re getting a tour of Undershaft’s “Death Factory”, when things really begin to heat up. That’s also when the domineering patriarch is hemming and hawing about finding a successor to run his business. His son prefers a career in politics (which allows for many a zinger). His daughter is busy saving the world with the Salvation Army. So, that leaves his son-in-law, a Greek professor.

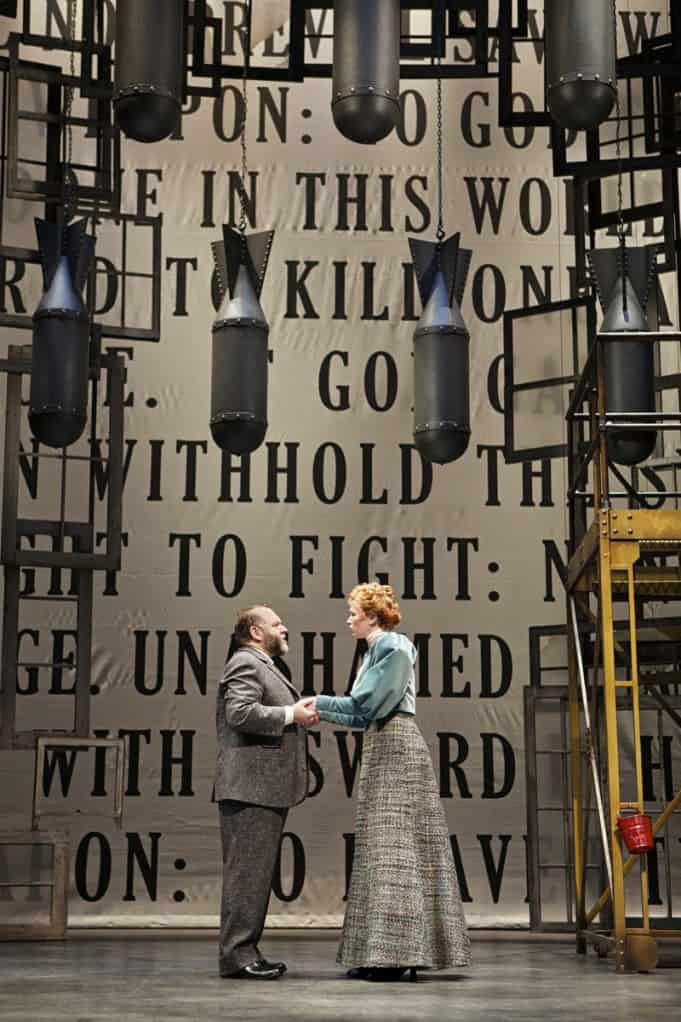

Staging at A.C.T. is almost always exceptional. Again, this production, with its soaring and rotating sets, is beyond reproach. There’s glittering snow, weathered window panes as far as the eye can see, and, later, haunting imagery of a war factory building weapons to destroy. The sets are so grandiose, and there’s so much for the eye to see that the actors are at times dwarfed.

The cast is decent, if uneven – at least on opening night. Blocking was not as smooth as perhaps as it will get over the coming weeks; actors often seemed awkwardly forced in their direction across the stage. Fortunately Dean Paul Gibson as the secularist Andrew Undershaft is superb in a role that sees him as equally absent-minded as it does relentlessly focused. He storms the stage, admonishing the soft for their puritan ways. “I’m a millionaire. That’s my religion!” He anchors this production, giving it energy, and pitch-perfect satirical resonance.

ALSO: Stark Insider Goes Inside Downton Abbey with Mrs. Patmore (VIDEO)

Earlier scenes in the play will no doubt draw comparisons to Downton Abbey. Though the action takes entirely upstairs, the class system is obvious fodder. Another contemporary example could be There Will Be Blood (2007), Paul Thomas Anderson’s magnificent film about capitalism, religion and the dangers of bowling alleys in homes.

What’s astonishing about Major Barbara, though, is its continued relevance. Do weapons, wars and violence give “common people” a possible equalizer in the struggle against “intellectuals”? If our systems, be they religious, political or social are broken, why don’t we re-think them rather than reinforce centuries-old thinking? And, if morality is to be based on character, who’s character shall it be based upon, yours or mine?

MAJOR BARBARA succumbs to Blood and Fire. What BioShock and this play have in common: https://t.co/qSvSZvsjdC #ACTBarbara

— Clinton Stark (@clintonstark) January 16, 2014