Officer Lockstock wasn’t entirely correct when he told Little Sally “Nothing kills a show like too much exposition.” This little gem from Urinetown might be true in the west, but as The Orphan of Zhao reveals, it’s far from universally applicable.

Such notions must have been on the mind of poet, literary critic, and political correspondent James Fenton, who wrote this adaptation of The Orphan of Zhao, which just opened at the A.C.T. in San Francisco. Since wholesale adoption of Chinese theatrical conventions would lack authenticity for a western playwright, he adapted the tale for a western audience, while rigorously following certain Chinese conventions. He speaks of this in an interview with Dan Rubin, saying, “The whole point of doing this piece was to give us a feel for classical Chinese theatre … so that when a character comes on stage, [he] introduces himself, and then says what’s on his mind or what his situation is.” In short, it follows a Chinese version of explication.

The object lesson for westerners is just how grippingly expressive this convention can be. In western theatre, there’s often a mediator to whom expository remarks are directed. Thus, you have Little Sally’s explication in conversation with Officer Lockstock in Urinetown, Tevye’s talking to God in Fiddler, and so forth. However, Fenton’s play bypasses such mediators; the result is naked emotion, non-manipulative and expressive. What might have otherwise been a cheap slice ’em, dice ’em suicidal thriller was rendered into something deeply emotive that probed the dimensions of loyalty and family.

ALSO SEE: A Criminal Venture at San Jose Stage Company

Being the first Chinese play to appear in the west, Orphan in all its various permutations, has been with us since the first French translation in 1731. However, this work goes way before then; Ji Junxiang penned the play during the Yuan dynasty (1271 – 1368), a time when Kublai Khan formalized Mongol domination as a conventional Chinese dynasty. However, this story probably existed hundreds of years earlier. In staging this play, A.C.T. brings us their unique take on established classics and should-be-classics, just as they did with “Venus in Fur,” “Elektra,” “The Normal Heart,” “The Suit,” and so many others.

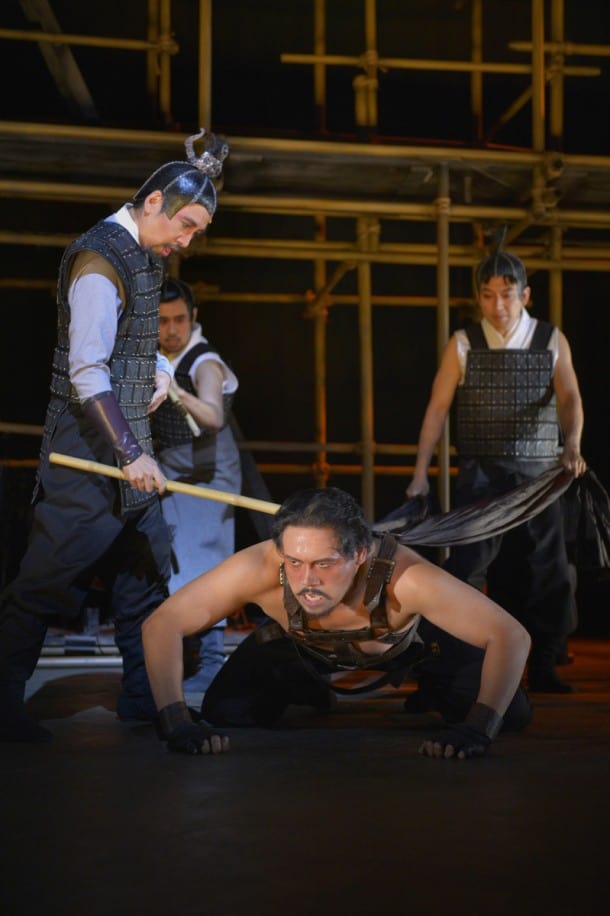

The Orphan of Zhao grips the audience from beginning to end thanks to a brilliant cast, thoughtful scenic and costume design, and haunting melodies performed on stage. BD Wong, (whose television credits include Law and Order, Mulan, Oz) brings us a sensitive and courageous Cheng Ying, who sacrifices himself and his son to bring the Orphan of Zhao back to court. Julyana Soelestyo is in relatively few scenes, yet her portrayal of Cheng Ying’s wife is an emotional center around which much of the show pivots. Stan Egi gives us a deliciously evil Tu’an Gu, whose acts provide the impetus from which the drama evolves. However, this Tu’an Gu isn’t a two-dimensional portrayal of evil; flickering moments of genuine feeling for his adopted son give him a depth that would otherwise be absent. Lithe and animated, Daisuke Tsuji, as Cheng Bo, adult orphan of Zhao, is so wonderfully different from the other characters, it’s easy to see how he alone is capable of redeeming the state.

MORE STARK INSIDER: So Long Friend: San Jose Rep declares bankruptcy

The set included a relatively spare, multilevel bamboo scaffolding. This uncluttered scenic design was appropriate for such an emotionally rich performance. Had the stage been cluttered with imperial regalia, and actors bedecked in dragon robes, the excess would have detracted from the emotion.

The Orphan of Zhao will be at A.C.T. through June 29th.This fast-paced show is worth taking in as Cheng Ying’s struggle will echo through your entire summer.