Moby Dick – Rehearsed is a curious play that gets produced far too seldom. One of Orson Well’s seeming cast-offs, it offers a play within a play within another play. Don’t be put off by this overworked device, however; the Stanford Summer Theatre (SST) may have changed its name to Stanford Repertory Theatre (SRT), but it continues a tradition of gripping theatre under the thoughtful direction of Rush Rehm.

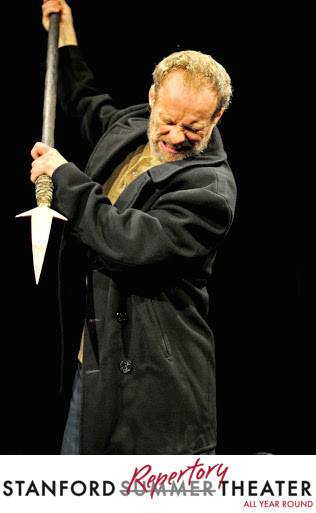

Part of the critical success of SRT lies in casting. Moby Dick – Rehearsed includes a mix of professional players, students and recent grads. This current offering includes Rod Gnapp (who looks more and more like a handsomely weathered George Clooney) and Courtney Walsh (who blew everyone away in SSF’s Happy Days and SF Playhouse’s Jerusalem). Don’t think for a minute, however, that Moby Dick – Rehearsed relies entirely on these tent poles. The overall cast – including Timothy James Borgerson as Stubb, Christopher Prescott Carter as Peleg, and Peter Ruocco as Starbuck – is far too accomplished to let that happen.

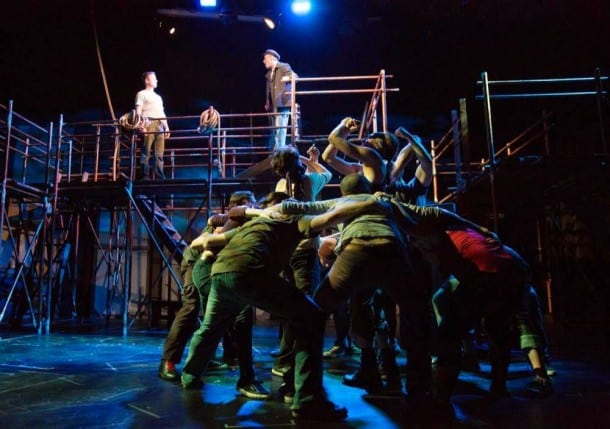

The play opens on an odd note with an equally odd set. A group of actors mill about complaining during a rehearsal break in a production of King Lear. The appearance of the director (Courtney Walsh) gives merit to their complaints as she starts demanding a “post dramatic, post modern” tone while insisting the actors pose in stereotypic “angles of alienation.” Complaints reach a fevered pitch and the director pointedly exits as canvas-covered flats (including one emblazoned with a primitively painted sun) get shoved aside to reveal a scaffolding that becomes the Pequod, a whaler out of Nantucket, as Louis McWilliams (Playwright / Ismael) utters some of the most famous first lines in all of western lit: “Call me Ismael.”

Director Rush Rehm finds parallels between this and the modern world. He notes that “the version that we’re doing is built around a theatre company that has in some sense lost its soul – and it finds itself in this great narration, in this great story.” According to Rehm, this isn’t just about the whaling ship, or even Ahab’s quest.

Rehm elaborates “There are many, many things Melville’s book has to tell us about the America we live in: our ambition, our greed, our commitment to some thing that we think will solve our problems – our quest for our own white whale.”

Broadly, energy on stage fits one of three patterns: the fierce, isolated intensity of Ahab, the compliant, but detached skepticism of Starbuck, and the intentionally unfocused direction of the rest of the cast. This tripartite energy division serves the action well, as does the movement and song peppering the production. While choreography might not be extravagant, blocking is remarkably effective, as it underscores the physicality of the cast on their particular quest.

This helps explain Gnapp’s somewhat puckish smile at the end, as to say “well, that play’s done” with the intimation that the Moby Dick drama was merely part of something bigger. Indeed, the only nit to pick is the ending itself, which, while resolving the Moby Dick story, leave the audience hanging regarding King Lear, and the actors themselves. However, this sense of incompletion is inherent in the work itself.

Moby Dick – Rehearsed runs through August 10 as part of the larger Stanford Orson Welles festival that includes a community symposium, film series and a staged War of the Worlds, which opens on August 14th.