Given the bona fides of Conrad Bishop and Elizabeth Fuller, I looked forward to their production of King Lear. However, staging a puppet version of Lear seemed wildly ambitious. How do two puppeteers handle almost 30 characters? How do they do it on a tiny puppet stage? How do you handle dialog between human actors (Bishop plays Lear and Fuller the fool) and their puppets without seeming like Captain Kangaroo talking to Bunny Rabbit?

If anyone could leap these hurdles, I reasoned, it would be Bishop and Fuller, the husband and wife team behind Independent Eye, who had traversed the distance between puppetry and Shakespeare in their productions of The Tempest and Macbeth.

The rationale for staging a puppet Lear isn’t as arbitrary as it seems. As the press release notes “Lear is the puppeteer of his own puppet show. In his mind, he is the only real human in his motherless kingdom of power and commodity, where love is merchandise for barter, quantifiable by the number of knights under his command.” While Lear is a failed puppeteer, unable to negotiate a mind unraveling, let alone pull the strings for his family and subject, this staging does allow the audience to come closer to how Lear saw himself.

Many non-traditional productions of Shakespeare involve some degree of time travel (like the brilliant Custom Made production of Merchant of Venice, in which characters were inseparable from their cell phones) or shifting geography (as the African-American Shakespeare Company did when staging Julius Caesar as a sequence of rotating African dictators. However, this traditional Lear (and this is a very traditional Lear) compresses space – that most vital element for actors.

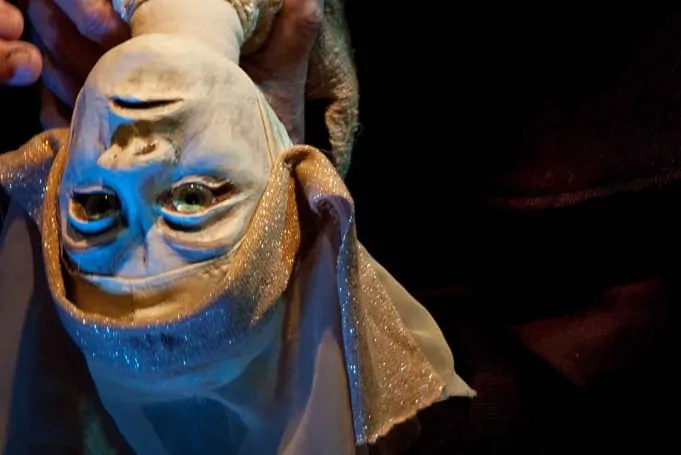

The roughly 7′ puppet space (not a Punch-&-Judy puppet stage) uses space as efficiently as a submarine. Two adults, 30 puppets (ranging from 5-6” little heads to fully fleshed out characters maybe 3’ tall), miscellaneous props, lighting, and a laptop are packed in.

The ratio of space to stuff was so high that one spends more than a few moments marveling at how seamlessly Bishop and Fuller worked together, handing puppets back and forth with the deftness of surgical assistant passing a scalpel. However this very deftness worked against them, being both bug and feature. While this husband and wife team worked together with enviable fluidity, all too often, my attention was drawn away from the play to watching them work their logistical magic.

Embodying all of the almost-30 characters was no mean feat. Not only did Bishop have to traverse the distance between himself as Lear and the puppet characters he voiced, he also had to traverse the distance between individual puppet characters. Fuller shouldered comparable burdens. In this regard, the Independent Eye’s could be a two-person variant of a one-man show. Just as the success of a one-man-show turns on a solo performer embodying distinctly different characters, so too the success of this two-person show turns. Here the performers lacked space – one of the key tools in the solo performer’s trade– and this lack of space worked against Bishop and Fuller. This was problematic in a work that is so much about distance.

In many respects, Bishop’s Lear was the best I’ve ever seen. His age (73) works in his favor, as does his physical persona, with long, flowing white hair and rheumy eyes. Working in a small space has the effect of amplifying the emotional tenor – and you’ll marvel at how much crazy Bishop can fit into the tiny stage.

However, when Bishop plays multiple characters rapid fire, edges blurred. If you’re unfamiliar with Lear (or haven’t reread it in some years), just getting a grip on the language poses enough of a challenge – without constantly asking “what character is talking now?”

Fuller too played multiple characters, but since she was onstage less, each character emerged more fully formed. Her characters seemed to rise from some deep part of her, each distinctly different and differently voiced from each other.

Fuller’s exceptional score, composed for this work, played unobtrusively in the background. This sound collage expanded the space a bit, taking the viewer beyond what was on stage. Scenic design had the same effect – perfectly complementing the action, but taking the viewer away from it.

King Lear will be at The Emerald Tablet through August 26th.