“It’s not good enough… I wasted six months of our lives.”

Nicolas Winding Refn held himself, once again, to a very high standard. The Danish director was coming off the smash film Drive and feeling the pressure that comes with the followup. In this case, that would be Only God Forgives (2013), most certainly, as he emphatically reminds all, not Drive 2.

Ultimately, it turned out to be a polarizing, art-house film that audiences either loved or hated — a sign, as Refn points out while reading out one particularly harsh review on his iPhone, indicative of cinematic success (that half love it, half hate it). Regardless of what you think of the moody revenge experiment, it is gorgeous to look at. And with Ryan Gosling as the lead, you get plenty of that irritated, brooding stare. Again, love it or hate it.

But as I discovered — thanks to this article ranking top 15 docs about making a film — what’s really most intriguing about Only God Forgives is the perpetually tortured process it took to make.

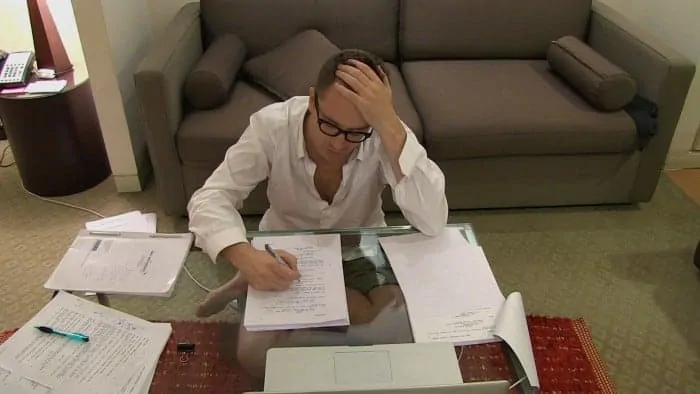

Remarkably, Refn allowed his wife, Liv Corfixen, to document its making (My Life Directed by Nicolas Winding Refn). She follows him around their temporary condo, with spectacular, sweeping views of Bangkok (feeling very much like L.A. in Drive actually). We watch as he struggles to piece together a storyboard of index cards (“it’s like Chess”) on the living room wall, takes a phone call with a producer, and later discusses with a wryly dubious Gosling the arcs of love and violence. Gosling apparently doesn’t buy it.

Though Drive was a commercial success, the budget on this project looked to be much tighter. In fact, in one memorable scene (and I almost can’t believe they left it in), Refn tells Gosling he’s been offered $40,000 if the two of them show up at a local Thailand film festival. It’s only two hours away. They could use the money. And he’s going to push for $100,000! In cash! Corfixen then follows the two as they head to the festival, and, sure enough, just like in the movies, pick up neatly stacked wads of baht. Refn actually starts counting it (just like Pacino in Scarface) before handing it to his money man. “We can use this for some special effects or something,” he says.

One of the reasons I suspect Refn has such a loyal fan base is because he’s a genuine risk-taker. In a cookie-cutter world of Hollywood sequels and infinite re-boots, what a rare gift it is to have someone who brings to the big screen (often writing and directing) films that might not otherwise make typical commercial sense, or pass mainstream sniff tests.

“It can’t be in between strange and normal.”

It’s probably no surprise that legendary auteur and mentor Alejandro Jodorowsky (El Topo, Holy Mountain) drops in for a few appearances. It’s quirky stuff involving Tarot cards. How appropriate, and at times even sweet.

“That’s when you know you’ve made great cinema. When half love it. And half hate it.”

As Refn continues to wrestle with his fears and doubts we get plenty of inside looks at the production. We see elaborate sets; in one scene Refn insists a gang shoot-out be painstakingly done over and over again (with the “reset” taking hours). There are massive technical aspects to making a feature film, and you get a glimpse into some of that here. But not much. Corfixen, smartly, is focused more on inner turmoil, and the creative process. For those of that love digging into the ethos of “directing” and “filmmaking” it’s mostly intriguing fare, even if Refn refuses to crack a smile until the final act.

As the conclusion builds, heavy rain begins to fall. Refn and the family are on the way to Cannes where Only God Forgives has been selected, and given the red carpet treatment. Is the rain an omen? “It’s only rain,” says his daughter, shrugging her shoulders.

“It would be boring if we all just made safe films.”

Indeed, the film world is a better place with people like Nicolas Winding Refn. Fortunately his wife affords us an expose — one often dark, brooding (just like his films) — into his headspace during a tumultuous project. Refn suggests great art stands the test of time. I remember listening to David Bowie’s experiment Tin Machine project in the 80s. It just would not click, even after repeated listenings. The same could not be said about U2’s masterful Achtung Baby, a tough initial listen given the U2 we thought we knew at the time — but one which revealed its many astonishing well-crafted layers over time. After watching this short documentary (58 minutes) I re-watched Only God Forgives. I looked at it very differently. It felt different. I can’t be sure how it will age, and how it will be perceived by future generations, but I do know this: Nicolas Winding Refn is no wallflower.

Look for My Life Directed by Nicolas Winding Refn on Netflix. Then watch Only God Forgives, followed by Refn’s crowning achievement Drive. Filmmakers, would-be directors and even fans of the creative process: take lots of notes.