Amazon uses “cost per first stream” to evaluate the success of its streaming shows. Here’s some thoughts on the internal metric and what it means for content producers.

Evaluating the success of television shows has been, for the most part, a fairly routine thing in the past. Led predominantly by the Neilsen ratings statisticians could easily determine how many people were watching a particular channel (show) at any given time.

But that was then. Now we have streaming options galore: Amazon, Hulu, Netflix, Vudu, Google, Apple, HBO app, Sling and, on and on. Networks like ABC, CBS and NBC still exist, though now they’re distribution is increasingly fragmented.

So I find the whole measurement of “ratings” for shows to be an interesting phenomena given the disruption were witnessing. It doesn’t seem to be so simple anymore.

Amazon has an interesting approach to measure the success of their (myriad) TV shows.

The metric is called “cost per first stream“.

Reuters revealed the detail behind its meaning and implementation. In short, the cost per first stream is the price (cost) to “hook” a customer on Prime (which requires a paid yearly membership to access).

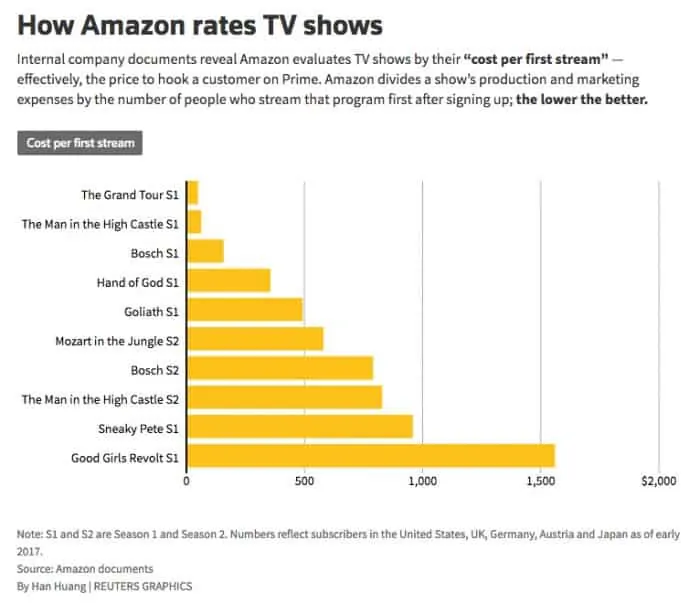

Per the article, “Amazon divides a show’s production and marketing expenses by the number of people who stream that program first after signing up.” The lower the number, the better the rating — and the better the likelihood the who would get renewed for another season.

You can read more about that on Reuters: Amazon’s internal numbers on Prime Video, revealed.

This so-called secret math attempts to determine why someone paid for a Prime membership, but figuring out what they first streamed after joining. This, goes the logic, must be why that particular customer paid for Prime. To see the very first show that person streams.

That makes sense and results in a very interesting way of normalizing data. In essence it’s a modern day equivalent of a Nielsen-like rating. Using Amazon documents, Reuters put together this chart which is a good way to see what shows are doing well on Amazon, and helping to drive Prime memberships:

Based on that metric you can see that shows that enjoyed successful first seasons included The Grand Tour, The Man in the High Castle, and Bosch. Coming out last, at least in this particular assessment was Good Girls Revolt.

Currently, an annual membership to Amazon Prime costs $99 per year. So if a show can attract a new subscriber for less than that, Amazon already nets a profit on that particular hook strategy. Conversely, a new show like Good Girls Revolt appears to be a boat anchor; its production and marketing budget well exceeds its ability to benefit new Prime memberships.

Reuters says, by its math at least, that The Grand Tour (the guys formerly of BBC’s Top Gear) cost only $49 per subscriber in its first year. That result would appear to justify the massive $78 million budget of that show. In the end, it built up new Amazon customers.

And this is just the tip of the analytical iceberg.

Can you imagine the amount of data mining going on at Amazon?

It’s one thing for a first click, but what about propensity to purchase products? Some shows probably attract more active shoppers than others. Why, I’m not sure. Amazon probably knows. And can somehow monetize our behavior on the site further based on that information.

Then, of course, there’s retention.

It’s one thing to click on the first episode. And, as we all know interest is fleeting. Some shows, no doubt, are better at retaining viewers all the way to the very end. I suspect Netflix has such a champion in its schedule in Stranger Things.

Given the massive battle for original content and viewership between heavyweights like Amazon and Netflix and Hulu and Apple among so many others, I suspect, too, that lose leaders aren’t out of the realm of possibility. Why not? My suspicion is getting that first subscriber is critical. If that person pays for Netflix first, for example, then shaking them loose to get them to change to, say, Amazon, is more difficult than if that person were not already a paying Netflix customer. Hooking a customer first is likely extremely important.

Now Amazon is pushing hard into blockbuster films. Given its (apparent) success in producing television shows, it will be interesting to see how — and it’s most definitely going to be a how and not an if — Amazon distributes the studio system for blockbuster films. Reuters notes that Jeff Bezos and team paid $250 million to make a prequel to The Lord of the Rings. And that $250 million? That’s only for the rights. That doesn’t include actually making the movie or marketing it. Big bets. Uh, yeah. I guess you could say that again.

Meantime, I’m looking forward to seeing what director Nicolas Winding Refn (Drive, Neon Demon) and his team cook up with their upcoming Amazon-backed show. It’s called To Old To Die Young and is slated for a 2019 release (die hard fans can watch live streams of actual scenes being shot on Facebook). Refn is aiming to “Make TV Great Again” so expect the series to be very Refn. And expect him to keep a close tab on how it fares when it comes to the “cost per first stream” test. Because Only Bezos Forgives… when that number doesn’t spiral out of control.