One of my favorite film movements is French New Wave. During the late 50s and early 60s, most notably, a handful of innovative and highly creative filmmakers rebelled against the sterile studio model — basic, but quality adaptations for the screen — and took to the streets of Paris with guerilla style production techniques.

Perhaps the best example is Jean-Luc Godard’s jump-cut fueled Breathless (1960). Several street scenes were shot without film permits. Look closely and you can see Parisians in the background look curiously toward the camera and crew as they shoot iconic scenes featuring legendary actors Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean Seberg. This was true indie spirit. And the results still standout today, some sixty years later.

If you’re a fan of film history, or just great films, you may want to check out the French New Wave era.

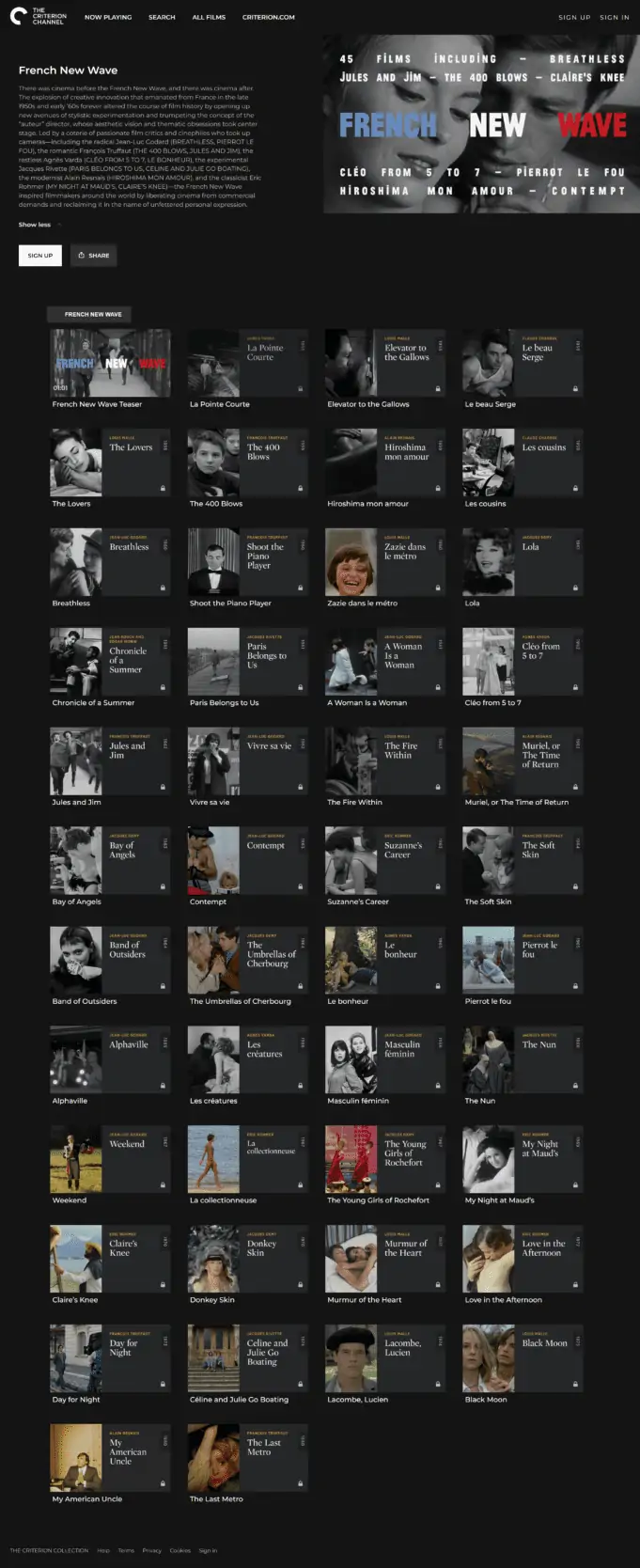

I stumbled upon this Criterion French New Wave collection and thought I’d share it here for those interested:

Tip: Mubi is another streaming platform to check out for these types of films.

Superbly curated in chronological order, you’ll not only find Godard, of course, but other trailblazers too including: François Truffaut; Agnès Varda; Jacques Rivette; Alain Resnais; and Eric Rohmer.

These innovative writer/directors forever changed film history — and even brought to light the somewhat controversial term “auteur.”

Look to modern filmmakers, say, like David Lynch, Wes Anderson, Daren Aronofsky, and Quentin Tarantino and it’s fun sport to spot French New Wave influence in their work; references here and there. Sometimes small, sometimes more significant. But they are there. And this is the beauty of watching filmmaking history build and evolve upon itself. (I should point out my examples here are clearly American, however the movement extended and continues internationally of course as well).

For instance, is it a coincidence that surreal masterpiece Mulholland Drive (2001) by David Lynch ends on the exact same line of dialog, “Silencio,” as does Contempt (1963) by Jean-Luc Godard? Or that one of its leading actors shares the same name (Camille/Camilla)? Or how about the key scene midway through in Contempt when the main characters watch a poorly produced musical performance with dreadful lip-syncing (parody?) accompanied by curious and random stop-start-stop sound design by Godard’s post-production team. Does this bear any similarity to the essential scene at Club Silencio in Mulholland Drive where too sound is fundamental to the viewer’s experience?

There’s so much more as well. The layers upon layers in which you can study, analyze and revel in this extraordinary time is pure magic.

Part of the joy of re-visiting these gems is to take in the beautiful scenery. Many of the films are set in Paris or the French countryside as expected. But there are exceptions featuring gloriously spectacular locations around the world. How on earth can cinematography be this good?

In Contempt (one of my favorites no doubt), then superstar Brigitte Bardot dazzles in a phenomenal performance, with the final scenes set against the Italian island of Capri at the famed Casa Malaparte — an historic piece of architecture dramatically perched above the Tyrrhenian Sea. This location would become so imprinted in cinematic lore that it would even inspire modernist fashion films such as those for Louis Vuitton (Emma Stone) and Saint Laurent (Kate Moss).