Cy Ashley Webb reviews Hershey Felder as Leonard Bernstein in Maestro at Berkeley Repertory Theatre.

I loved Hershey Felder’s George Gershwin, Alone, one of the four musical theatrical biopics that Felder performs. However, as soon as I learned these four included Maestro, a show about American conductor and composer Leonard Bernstein, it skyrocketed to the top of my “must see” list.

Including Bernstein among his subjects seemed the height of audacity, not the least because Bernstein remains a living presence for many of us who revere him. Not only is he one of the very few classical superstars, he’s the only one on a first name basis with his audience. While we never think of Michael or Seiji or Herbert, we instantly know Lenny, even 24 years after his death in 1990. More than any other, he’s the conductor that belonged to us. For decades, he was everywhere, even conducting at the fall of the Berlin Wall (a recording available on Deutsche Grammophon).

The plausibility of Felder’s performance grows on you.

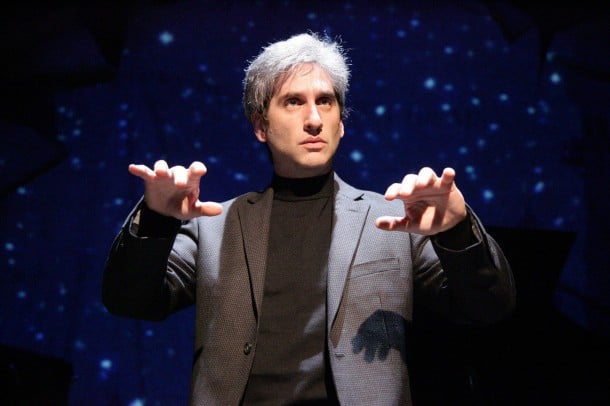

All of this is a long way of saying that Felder had his work cut out for him. However, watching Felder, with dyed grey hair (albeit combed far more neatly than Bernstein’s ever was) walk to the piano to play “One Hand, One Heart,” I was curious what physical attributes Felder chose to adopt, so perfect was his aping of the maestro’s physical mannerisms. A friend objected mildly to the initial staginess of the voice, but this seemed to miss the mark. Bernstein’s affected orotund voice was stagy; assuming biographer Joan Peyser is correct (and there being no reason to believe otherwise), Bernstein intentionally modeled his voice on that of the family rabbi, H.H. Rubenvitz. The only thing missing from Felder’s performance was Bernstein’s omnipresent cigarette.

Maestro will have few surprises for Bernstein fans. Don’t go looking for any dirt about Bernstein the monster (Peyser recounts Bernstein’s terrifying habit of giving everyone wet kisses, and then telling recipients that if either of them had AIDS, they both had it now); this is Bernstein the myth, told by the mythmaker himself. While the stories of Copland, Koussevitzky, Reiner,and Mitropoulos may be familiar, they’re worth hearing again, especially while proffered up with Felder’s capable hands rarely straying far from the keyboard. New to me was Felder’s (or is it Bernstein’s?) assertion that his musical roots are found in father Sam’s love of nigunim, those often wordless tunes beloved by the Hasidim.

Felder doesn’t pretend to have an exhaustive take on his subject. While purists might object to the omission of “Trouble in Tahiti” and “Mass,” including them could have easily made the show drag. Moreover, neither speaks to the essential Bernstein.

The plausibility of Felder’s performance grows on you. A friend remarked that by mid-show that he was convinced he was seeing Bernstein, instead of some Bernstein impersonator. Watching Felder’s Bernstein conduct the Vienna Philharmonic play Wagner, you’re immediately in the moment, understanding perhaps, for the first time, Bernstein’s take on something so hugely heroic.

More Theater & Arts on Stark Insider:

Wrong’s What I Do Best at San Francisco Art Institute (Video)

Freak Flag Alert: Shrek Musical coming to Berkeley

Sex and Dinos and Rock & Roll: Triassic Parq

Motivated in equal parts by pure love and pure narcissism, this composer, conductor, teacher, and master of the moment will not come this way again. While Bernstein left a universe well populated with his protégés (including Michael Tilson Thomas and Seiji Ozawa), Felder may be the best link we have to channeling the magic that is Bernstein.