“This is why you see live theater. It sticks with you, haunting, and beautiful. At its best, it shines an inspiring, if not at times challenging, light on our own lives.”

Chester Bailey is the kind of play you wish everyone had the opportunity to see. At its core, this world premiere probes the essence of humanity, and the delicate balance between truth and reality, and what it means to dream even under the most dreadful, dire circumstances. In other words: Joseph Dougherty’s Chester Bailey in an emotional wallop. If you see one play this year, see this one.

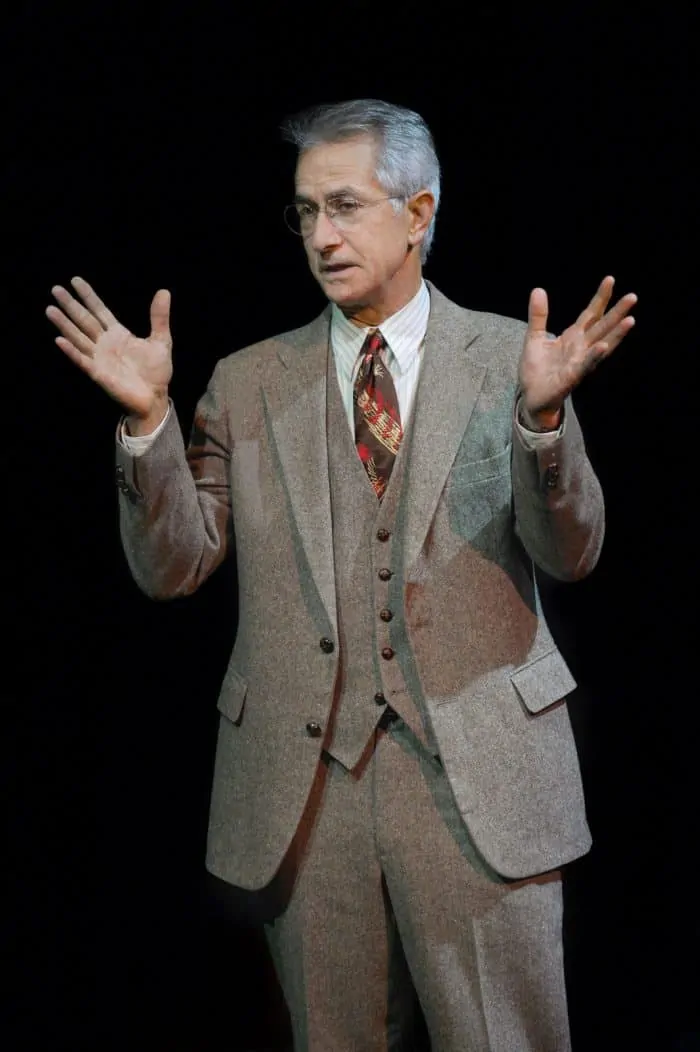

Film and television veteran David Strathairn is Dr. Cotton, a demure, charming, and accomplished professional eking out a traditional living in post-war Long Island. He counsels returning soldiers, trying to “take that look out of their eyes.”

Having suffered a tragedy at the dockyards, Dan Clegg’s Chester Bailey finds himself under Cotton’s care at the local hospital. Chester has lost his sight, and the use of his hands due to an accident. Or has he? Medical professionals say it is most certain, and, yet, the eternally optimistic dreamer swears his vision is slowly coming back. He sees rays of light, and eventually begins to recognize humans as shadowy figures. And, remarkably, he discovers he can even make out details in a painting on the wall across from his bed. A miracle in the making.

Acting here is nothing short of stellar.

Anchored by a lifetime of process and pragmatism, Dr. Cotton is naturally skeptical.

Later, when his patient is transferred to another institution, as he jousts with Chester Bailey, exchanging life experiences and probing backstory, we slowly realize there is more going on than initially meets the eye. Chester is head-over-heels in love for a red-headed girl he spotted in Penn station before his accident (magnificent set design by Nina Ball and lighting by Robert Hand), and is convinced she still visits him in the hospital at night — unbeknownst to all.

Unraveling the mystery of Chester Bailey and his new-found clinical environment is part of this play’s magic. And even if you figure out the twists and turns, the final scene between the two actors is one of the most powerful, most poignant I can recall seeing in the theater in the last decade here in San Francisco.

Acting here is nothing short of stellar.

Strathairn (who I most readily recall as Tom Cruise’s brother in the film adaptation of The Firm) is understated, earning our trust early. He’s a man of his convictions, yet, he too is fallible.

Clegg, a graduate of the A.C.T. MFA program, embraces his inner Long Islander. The accent, boyish body language, exaggerated facial expressions — all conspire to make us want him to get the girl, and to overcome his physical condition, and to discover clarity through all the morphine.

I’m particularly fond of shows, movies, and books that probe and explore the psychological condition. It’s one thing to show an explosion, a kiss, or an out-of-control car careening towards a newsstand (er… sushi stand?), but to make entertainment out of the inner workings of the brain, that’s something. Black Swan is one of my favorite such works. Director Darren Aronofsky gives us a narrator who may or may not be operating at full capacity. Yet the threat of conspiracy is genuine. The real and the imagined intertwine, before boiling over in a final reveal. This play is not an exact analog, to be sure, but it falls into that especially challenging style of work that delves far deeper than would first appear, inviting us to connect the dots, and interpret narrative based on our own life experiences and perspectives. The literal be damned.

Beautiful, poetic journey of discovery. In the end it is us who can see & our hearts that can feel. Bravo @ACTSanFrancisco! #ChesterBailey

— Loni Stark (@lonistark) June 4, 2016

In this era of extreme social media reaction, when we heart some thing, and then flip into full-on internet rage a minute later for another thing, I see the character Chester Bailey somewhat as the anti-millennial. He’s beset by one tragedy after another. His is a devastating life of epic proportions. Fairness is not part of the hand he’s been dealt. And, yet, through it all, he’s the most positive life force you’ve ever encountered. Denial? Maybe, hard to say — you’d have to see the play to draw your own conclusion.

To again borrow words from my wife, who said (well, tweeted) after the show as we walked out onto Market Street on a balmy San Francisco evening:

Chester Bailey is a “beautiful, poetic journey of discovery. In the end it is us who can see & our hearts that can feel.”

And this is surely one of the best world premieres in recent memory. Long live the imagination!