Near the middle of Needles and Opium, there’s a passage where Jean Cocteau criticizes critics. They never manage to understand, he explains, because they’re always trying to read meanings that aren’t there. Since it’s clear writer-director Robert Lepage identifies with Cocteau (they’re played by the same actor), I suddenly felt self-conscious about my past and future criticisms of Lepage.

I haven’t been convinced by previous encounters with Lepage’s direction (the Ring cycle and L’amour de loin at the Metropolitan Opera). His high-tech, minimal productions left a void that called for an interpretation without hinting at what it should be. The machinery felt clunky and got in the way of the drama. A Twitter friend snarkily pointed out that someone should tell Lepage that it is a valid staging choice to put actors on a flat stage and have them walk around.

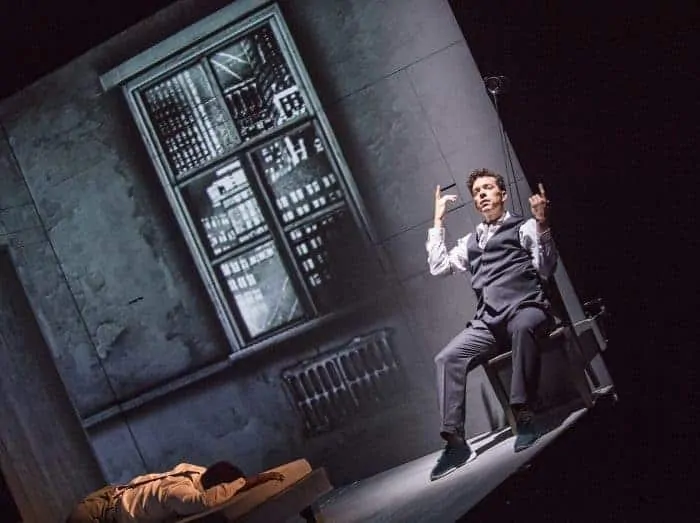

There’s no walking around on flat stages in Needles and Opium, either, but that’s as it should be. For this show, written, conceived, directed, and originally acted by Lepage, the centerpiece is a cube. Through intricately detailed projections, it becomes a dingy hotel room, a New York City back alley, a hypnotist’s office, and a recording studio. Windows and door slam open and shut. Oh—and the whole cube rotates. The actors maneuver their spinning word gracefully, sometimes with the aid of cables and sometimes simply with clever positioning. (Fred Astaire’s walls-and-ceiling dance in Royal Wedding came to mind.)

The actors maneuver their spinning word gracefully, sometimes with the aid of cables and sometimes simply with clever positioning.

The production’s deft use of technology gives this show a major “wow” factor. But that’s not all there is to it. The cube serves the story, which shifts between times and places to show the connections between three artists’ lives. Robert Lepage is in Paris trying to recover from a breakup. In 1949 in the same hotel, Miles Davis loved and left the singer Juliette Gréco. Meanwhile, French poet and filmmaker Jean Cocteau was in New York for the ill-received premiere of his film Eagle with Two Heads. He, too, suffered from lost love. Both Davis and Cocteau turned to opium. Lepage turns to hypnosis instead—but all must find ways to go on creating art in spite of heartbreak.

Wellesley Robertson III is a powerful, silent presence (except for the trumpet) as Miles Davis. Olivier Normand, as both Robert and Jean Cocteau, gets all of the words and all of the humor. He holds a lot of one-way conversations (on the telephone and with invisible directors) where his crisp manner and perfect timing give a subtle but clear indication of how exasperating the other person is. His studio recording session as Robert and his four-armed photo shoot as Cocteau are particularly funny. He also provides the emotion. Davis and Cocteau are background; it is Robert’s anguish that provokes painful sympathy.

Recent Theater Reviews

By Ilana Walder-Biesanz

Despite the twinges of despair, the lasting impression of this play is wonder. Wonder that these artists’ stories have such parallels. Wonder that they can combine to form one cohesive, moving piece of theater. And wonder at how the production’s technological wizardry is managed.

Needles and Opium

A.C.T. San Francisco

5/5

Photo credit: Tristram Kenton and Nicola-Frank Vachon