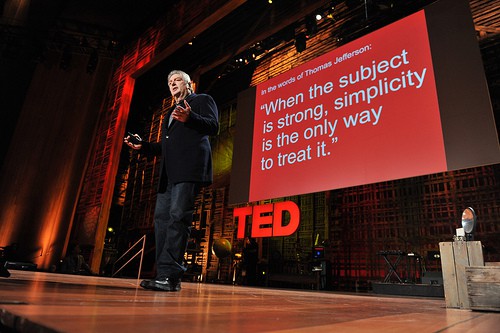

After interviewing Philip K. Howard on his experience speaking at TED and his latest book ‘Life Without Lawyers: Restoring Responsibility in America’, I was intrigued to read his written work which arrived in the mail a few weeks later.

After interviewing Philip K. Howard on his experience speaking at TED and his latest book ‘Life Without Lawyers: Restoring Responsibility in America’, I was intrigued to read his written work which arrived in the mail a few weeks later.

It didn’t take very long before I realized I had the same foreboding feeling I had when I first read 1984 in high school. The only difference here is that what Howard paints is a perspective on current society, not a projection into what may be if we continue down a particular path. Through the lens that he provides, we see our world as one in which the human spirit and accountability are being strangled off by the tentacles of an overly convoluted legal system.

We are first introduced to the purpose of law and legislation in our society and the evolution of it through the decades. Howard makes an important point that society has changed, yet the response with each change has been the laying of additional rules and regulations; there is no assessment of what laws may not be needed. The result of such behavior is an overly complex legal system—a Frankenstein of good intentions gone bad.

We are first introduced to the purpose of law and legislation in our society and the evolution of it through the decades. Howard makes an important point that society has changed, yet the response with each change has been the laying of additional rules and regulations; there is no assessment of what laws may not be needed. The result of such behavior is an overly complex legal system—a Frankenstein of good intentions gone bad.

In each chapter, he marches out horror stories of individuals who strive to build businesses, play on jungle gyms, care for patients and teach children who struggle because of a legal system that values individual rights over everything else, including the common good of the majority. In some of these cases, the protagonist (a doctor or an owner of a dry cleaning business) does prevail after many years of court trials and several hundred thousands of dollars in legal fees defending against frivolous claims. However, in these cases, such a victory does not prevent a spirit being broken.

I found Howard’s analysis of the impact of the legal system on our education and health system to be fascinating. Not only does he give specific examples of teachers who can’t discipline students for fear of a lawsuit and doctors who prescribe treatments based on likelihood of legal complications, he demonstrates how such incidents on a grand scale are the key reasons for runaway costs and poor results.

Howard defends the use of judgment and common sense pointing to examples such as the Charles Cullen, a nurse who was suspected by many co-workers at the different hospitals he worked at as not quite right. He was later found to have probably murdered more than forty patients. Many of the doctors and colleagues suspected there was something not right. However, because of legal liabilities, they were only able to say, “We confirm that he worked here from this to that date.”

The most depressing part of the work was Howard’s indictment of Washington and the government. He takes a bipartisan stance on how the efforts and decisions in Washington have little to do with the common good. Instead, he claims it is a place strife with political battles and special interests. He even recounts a story where the ultimate decision made was to make the other party look bad instead of working on a bipartisan solution to benefit the citizens.

This is not a feel good book. However, it is a must read for anyone remotely interested in public policy and the steps we must all take to restore sanity in our education, health and political systems.